Why Test?

There are a number of reasons to test your cattle for Johne’s disease. And, that there are times when testing for MAP (the organism that causes Johne’s disease) may not be needed. The best test for your herd situation depends on what the testing information will help you accomplish. Diagnostic testing can help:

- Determine whether or not MAP is present in your herd.

- Estimate the extent of MAP infection in a herd, called the within-herd prevalence.

- Control MAP in a herd that is know to be infected.

- Make a diagnosis for an animals showing clinical signs typical of Johne’s disease.

- Discover if MAP is present in the farm environment.

- Meet pre-purchase or shipping testing requirements.

Once your veterinarian knows the reason(s) you want to test for Johne’s disease, they can tailor a testing program that best meets your needs. This program should outline the type of test, when to test, which animals to focus on, the cost of testing and how to interpret the results.

For any of these diagnostic assays, it is best if and your veterinarian use a laboratory that has voluntarily taken (and passed!) an annual “proficiency test” to confirm that their methods are valid. The list of laboratories that have passed the US proficiency test for Johne’s disease can be found here. Note: labs are listed by type of test – not all laboratories perform every test. The link below lists labs approved for: 1) Serology (antibody-detection tests), 2) organism-based methods (PCR or culture), and 3) tests that use sample pooling.

Which Test Should I Use?

The two primary types of diagnostic tests look for either the organism that causes Johne’s disease (MAP, Mycobacterium avium subspecies. paratuberculosis) or the animal’s response to infection by MAP (antibody in the blood or milk).

Organism-based tests.

There are two types of these assays: (1) Culture, which isolates the living MAP organism itself from manure, tissue or environmental samples and (2) PCR, which looks for the MAP genetic material from living or dead MAP.

1. Culture:

A sample submitted for culture is monitored for eight weeks or longer because MAP is a very slow growing organism. If the sample is heavily contaminated with MAP, a positive result may be had sooner, but it can take two months of incubation or more until the lab feels confident that no MAP organisms are present and can report a “culture negative” result. Culture is effective for testing any animal species (manure or tissue samples). Pooling of manure samples reduces the cost of a herd test. Individual samples are collected, then the laboratory mixes the samples (usually 5 samples per pool, 1 pool per culture). If a pool is test positive, the 5 animals contributing to the pool are then tested individually to find which one(s) are shedding MAP. Older culture methods used solid culture media that were examined visually on a weekly basis for at least 3 months. Newer methods use liquid culture media and automated instruments to “read” the culture for up to 8 weeks.

2. PCR, also called direct PCR: This test is used on manure samples. The assay looks for MAP’s genetic material instead of the living organism. Most labs provide a result in less than a week. The accuracy of culture and PCR are comparable.

Paraffin block PCR is a special form of PCR that only some laboratories perform. When tissues are collected at a necropsy, they are embedded in paraffin to be thin-sectioned, stained and examined microscopically. The pathologist is looking for damage to the tissues and for MAP itself within cells. Your veterinarian can request a PCR test on a portion of the paraffin block.

Paraffin block PCR is a special form of PCR that only some laboratories perform. When tissues are collected at a necropsy, they are embedded in paraffin to be thin-sectioned, stained and examined microscopically. The pathologist is looking for damage to the tissues and for MAP itself within cells. Your veterinarian can request a PCR test on a portion of the paraffin block.

Most labs also use a PCR to confirm that the organism isolated during culture is actually MAP vs. one of its closely-related cousins.

Antibody (blood or milk) tests

These assays look for antibody produced by an infected animal using a technology called ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay).

ELISA

To perform this test, 2-3 milliliters of blood or milk is collected from an adult animal. The fluid part of blood samples (serum) is tested for anti-MAP antibody. The amount of antibody found (if any) is compared with positive and negative controls, and an interpretation is then assigned to the ELISA result. These numeric results (the actual amount of antibody) are useful: the higher the test result, the greater the certainty that the animal is infected and shedding MAP.

The ELISA is designed for testing large numbers of samples quickly (a few days) and this makes it a low-cost test. A number of ELISA kits have been approved for use in milk from individual cows as well as blood samples.

ELISAs are popular because they are fast and the least expensive of the available tests for Johne’s disease. However, they are designed for rapid, low-cost screening of large number of animals. ELISAs are less sensitive than MAP-detection assays (PCR and culture), detecting roughly one-third of the animals that MAP-detection assays will identify as MAP-infected. This is generally because antibody production occurs later in the course of a MAP infection, months or even years after an infected animal has been passing MAP bacteria in its feces.

ELISAs are >99% specific. This means that there is a <1% chance that a positive ELISA is a false-positive. Typically, this means that animals found ELISA-positive should have a confirmatory test done by PCR or culture.

There are many nuances to testing recommendations, particularly related to dairy cattle and use of milk ELISAs. All of these nuances cannot be explained here. The best advice is to discuss your specific needs for Johne’s disease testing with your veterinarian.

Regardless of which cows you test or which samples you collect, PLEASE package them with care!

Excellent shipping information is found on this WVDL page.

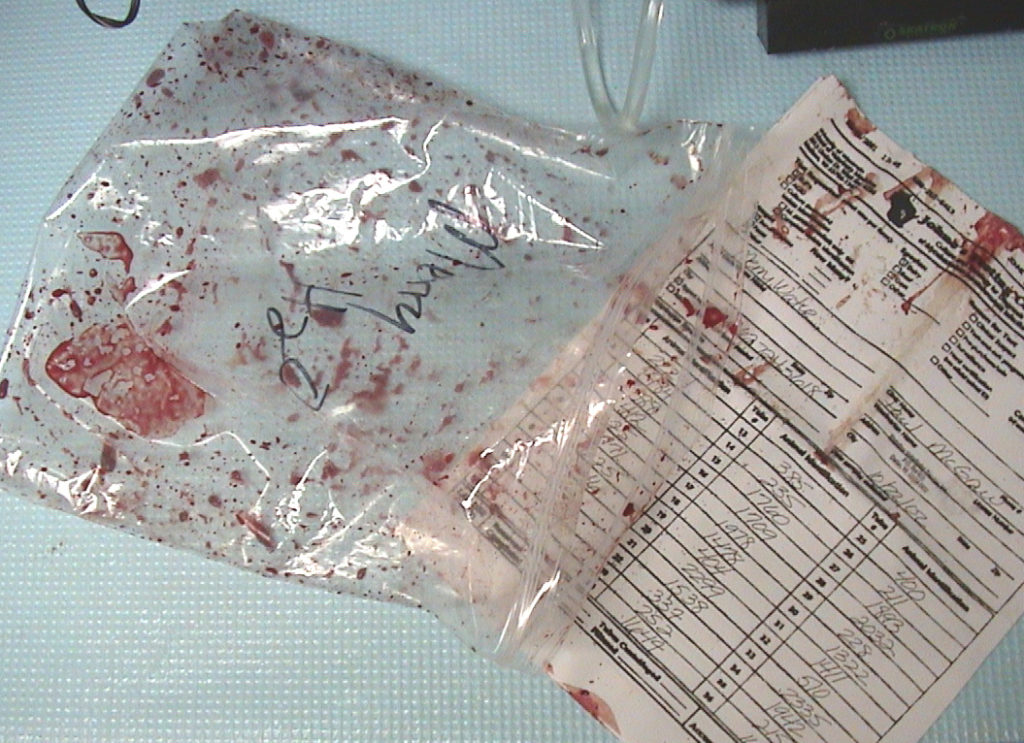

To make my point, below are some examples of what poorly packaged samples look like when they get to the laboratory.

Snap top tubes pop open when fecal samples ferment producing gas in transit to the lab causing cross-contamination of samples making it very hard to reliably test them.

Without sufficient packing material glas tubes will break in transit to the lab.

Submission forms accompanying the samples should be in a separate sealed plastic bag to insure it is readable on arrival to the lab.