Host range

Ruminant species (hoofed herbivores with four-chambered stomachs that chew their cud) are the natural host for and most affected by Mycobacterium avium subspecies. paratuberculosis (MAP). All genera of this diverse and numerous taxonomic group are believed susceptible to infection (pseudo-ruminants such as camelids as well). In ruminants, the infection eventually proceeds to gastrointestinal disease and death. This is true for domestic agriculture ruminants (such as cattle, sheep and goats), ruminant wildlife in captivity (e.g. deer, elk, eland, and muntjac) plus free-ranging ruminants including bison, elk, moufflon and guanaco. Cases of Johne’s disease (the clinical illness that appears months to years after initial infection by MAP in young animals) have been reported in every country in the world that has tested for it. The infection can spread from one ruminant species (for instance cattle) to another (goats, sheep, etc.).

Ruminant species (hoofed herbivores with four-chambered stomachs that chew their cud) are the natural host for and most affected by Mycobacterium avium subspecies. paratuberculosis (MAP). All genera of this diverse and numerous taxonomic group are believed susceptible to infection (pseudo-ruminants such as camelids as well). In ruminants, the infection eventually proceeds to gastrointestinal disease and death. This is true for domestic agriculture ruminants (such as cattle, sheep and goats), ruminant wildlife in captivity (e.g. deer, elk, eland, and muntjac) plus free-ranging ruminants including bison, elk, moufflon and guanaco. Cases of Johne’s disease (the clinical illness that appears months to years after initial infection by MAP in young animals) have been reported in every country in the world that has tested for it. The infection can spread from one ruminant species (for instance cattle) to another (goats, sheep, etc.).

Non-ruminant species (omnivores, carnivores) are infrequently infected, and few of these infections have been shown to progress to either clinical illness or systemic pathology. In these “atypical” hosts (such as fox, stoat, badger, raven, etc.) the organism is believed to be acquired through eating infected prey. While insufficient research has been completed to make any firm conclusions, it is believed that these non-ruminant species are “dead-end” hosts i.e. that the infection is not shed in the feces or milk to represent a risk of transmission and that offspring do not become infected in utero. There have been a few reports MAP infecting pigs, horses, and nonhuman primates. (See this page for more on infection of non-ruminants. See the Zoonosis section for a discussion of whether MAP represents a health risk for humans).

One non-ruminant type of animal does appear affected by MAP infection: rabbits and hares. There has been extensive investigation of a location in Scotland where rabbits have not only been infected by the same strain as MAP as found in the dairy cattle sharing pasture, but appear to maintain the infection in subsequent generations without re-infection from cattle or the environment. In some of these rabbits, MAP caused pathologic lesions resembling Johne’s disease. MAP infection of rabbits and hares in other countries has been reported as well, but subsequent disease is rarely described and these populations do not appear to be reservoirs of the infection as is seen in Scotland.

Prevalence

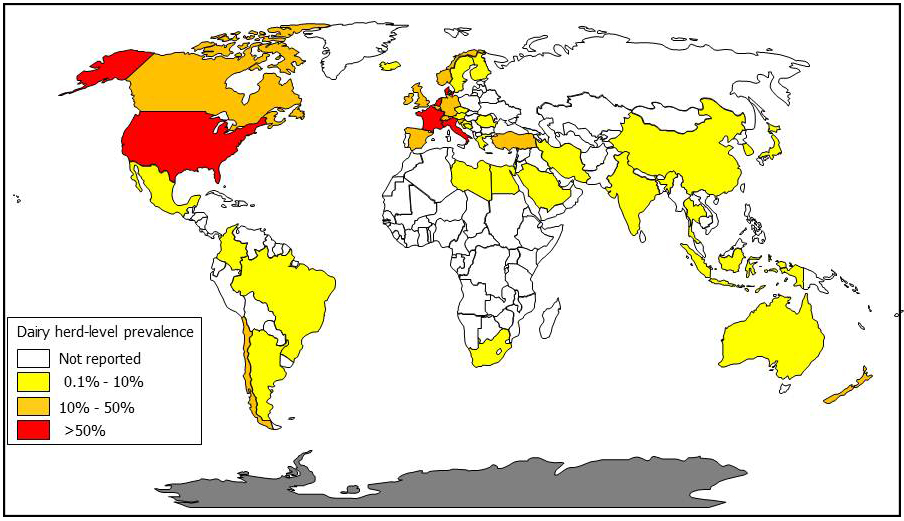

Dairy cattle herds have the unenviable honor of having the highest rates of MAP infection among domestic animals. Among U.S. dairy herds 68% were found to be culture-positive for MAP in 2007 yielding an estimated true herd-level prevalence of over 90% (when accounting for herds with false-negative culture results; Lombard, Prev.Vet. Med. 108:234-238, 2013). In Europe, the herd-level prevalence is over 50% with dairy herds being more commonly infected than beef cattle herds. The “best guess” prevalence for European sheep flocks was over 20%. European data come from an excellent review article by Nielsen (Prev.Vet.Med. 88(1):1-14, 2009). Only Sweden can claim to be free of MAP-infected cattle based on rigorous veterinary surveillance efforts, although imported cases of Johne’s disease have occurred.

A Canadian survey, reported in 2018, tested 362 dairy farms in 4 regions using environmental culture to estimate true herd-level MAP infection prevalence. The infection rates were: 66% for farms in Western Canada, 54% in Ontario, 24% in Québec, and 47% in Atlantic Canada. Herds housed in tiestalls had lower prevalence than freestall-housed herds, and herds with 101-150 and >151 cows had higher prevalence than herds with ≤100 cows (C.S. Corbett. Prevalence of Mycobacterium avium ssp. paratuberculosis infections in Canadian dairy herds. Journal of Dairy Science, 101(12):11218-11228, 2018).

A Canadian survey, reported in 2018, tested 362 dairy farms in 4 regions using environmental culture to estimate true herd-level MAP infection prevalence. The infection rates were: 66% for farms in Western Canada, 54% in Ontario, 24% in Québec, and 47% in Atlantic Canada. Herds housed in tiestalls had lower prevalence than freestall-housed herds, and herds with 101-150 and >151 cows had higher prevalence than herds with ≤100 cows (C.S. Corbett. Prevalence of Mycobacterium avium ssp. paratuberculosis infections in Canadian dairy herds. Journal of Dairy Science, 101(12):11218-11228, 2018).

The reported prevalence of infected animals by country is at least partially a reflection of the diligence with which veterinarians and animal owners look for the disease and the capacity of laboratories to diagnose the infection. The infection is much more common in dairy cattle due to prevailing animal husbandry methods that result in high animal density and multiple routes of concentrated MAP exposure for youngstock.

Sources of infection

MAP is an obligate animal pathogen. This means that the only place they can multiply in nature is inside an animal (ruminant). Most accurately, it is inside cells that are part of the animal’s immune system called macrophages. When MAP leaves an animal, for example in the feces, it can survive at low numbers for a long time (up to a year) in environments such as soil and water, but it cannot multiply there. Consequently, the primary source of infection is infected animals’ manure (and the resultant contaminated environment) and milk.

As MAP infection progresses in an animal, the frequency and number of bacteria being excreted increases. Cattle produce more than 100 pounds of manure a day and what to do with it is a big problem for the agriculture industry. This contaminated manure may be used as fertilizer for crops, be injected into the soil, be placed in lagoons, or run off pastures or fields into streams, ponds and groundwater. This means that the environmental burden of MAP can increase, and can spread beyond the farm. For more detailed information on the survival characteristics of MAP – see the part of this website called “Biology of MAP”.

Milk from infected female animals is a second source of MAP infection. Just as with fecal shedding, the likelihood of MAP being excreted into milk increases with time as the infection progresses. MAP may be excreted directly into the mother’s milk and/or the surface of the teats might be contaminated with infected manure. The probability of young animals becoming infected by drinking milk from infected cows a direct function of the time spent with the mother and/or how often they are fed milk from infected females. When contaminated milk is pooled, more young animals may be exposed.

Transmission of infection

Most MAP transmission occurs from adult infected animals to young calves through the fecal-oral route. The organism is swallowed in manure-contaminated milk, water or feed; sometimes manure is swallowed directly. MAP is also shed directly into the milk and colostrum of infected cows in later stages of infection, providing another route of exposure for susceptible young animals.

Another transmission route is in utero: a fetus may become acquire the infection from its infected dam even before it hits the ground. (Read this 2009 review by Whittington for more details.) The clearest example of this was an embryo transfer case managed under the strictest of research biosecurity conditions to prevent any exposure to MAP after birth (e.g., C-section birth and removed immediately from recipient cow, colostrum and milk collected from a different cow that was repeatedly test-negative bottle-fed, hay from uninfected herd pastures, etc.). While the embryo recipient cow was Johne’s disease test negative at the start of the pregnancy, it became strong ELISA-positive result in month six. After the C-section, the recipient cow was proven infected at necropsy. Two years later, the (very valuable) embryo calf was ELISA-positive and MAP infection was confirmed at necropsy. The recipient cow had been purchased from a herd with a history of Johne’s disease.

There is no transmission risk through nose-to-nose fence line contact (unless contaminated manure is sluicing under the fence), through sneezed aerosols, or via artificial insemination or natural breeding. The most likely way MAP initially enters a herd is when a silently infected animal is purchased and introduced.

These transmission factors form the basis of MAP infection control: protect the future of your herd (the youngsters) by making sure they are not exposed to potentially contaminated adult manure or unpasteurized milk from potentially infected animals. The extent and duration of exposure to contaminated manure and milk from infected adult animals directly affects the likelihood of sufficient MAP transmission to cause a new case of infection. Clean, dry, birthing environments and housing of young animals away from the adult herd or flock limits the possibility of infection transmission. Conversely, dirty maternity pens or fecal contamination of feed and water supplies will promote spread of the infection.