This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

What causes Johne's disease?

Johne’s (pronounced “Yoh-nees”) disease and paratuberculosis are two names for the same animal disease. Named after a German veterinarian*, this fatal gastrointestinal disease was first clearly described in a dairy cow in 1895.

A bacterium named Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (let’s abbreviate that long name to “MAP”) causes Johne’s disease. The infection happens in the first few months of a calf’s life but the animal may stay healthy for a very long time. Symptoms of disease may not show up for many months to years later. This infection is contagious, which means it can spread from one animal to another, and from one species to another (cows to goats, goats to sheep, etc.)

MAP is hardy – while it cannot replicate outside of an infected animal, it is resistant to heat, cold and drying. See “Biology of M. avium subspecies paratuberculosis” for more information about this bacterial pathogen.

(*Dr. Heinrich Albert Johne; follow the paths taken by scientists to understand Johne’s disease on the History page)

What kinds of animals get Johne's disease?

Johne’s disease is primarily a health problem for ruminant species (ruminants are hoofed mammals that chew their cud and have a 3-4 chambered stomach) and occurs most frequently in domestic agriculture herds. Some of the more common ruminants are cattle, sheep, goats, deer, antelope, and bison. It is particularly common in dairy cattle, not because they are more susceptible to infection but because they are more frequently exposed to the organism that causes Johne’s disease (MAP). Infected ruminants have been reported from all parts of the world. Non-ruminants such as omnivores or carnivores (birds, raccoons, fox, mice, etc.) may become infected, but it is uncommon for them to become sick because of the infection.

What are the signs of Johne’s disease in dairy cattle and what causes them?

There really are only two clinical signs of Johne’s disease: rapid weight loss and diarrhea. The infection occurs in calves in the first months of life, but signs of disease usually do not appear until the animals are adults. Despite continuing to eat well, MAP-infected adult cows become emaciated and weak. Since the signs of Johne’s disease are similar to those for several other diseases, laboratory tests are needed to confirm a diagnosis. If a case of Johne’s disease occurs, it is very likely that other infected cows (who may still appear healthy) are in the herd.

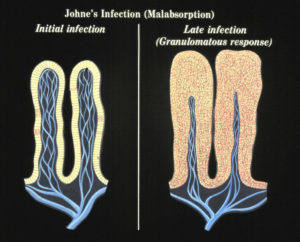

No one yet understands what causes a clinically normal cow that has been infected by MAP for months or years to suddenly become sick from the infection. We do know that at some point the MAP that have been lying quiet within cells of the last section of the small intestine (called the ileum) start to replicate and take over more and more of the tissue. The bovine immune system responds to all these organisms with what is called granulomatous inflammation. This inflammation thickens the intestinal wall, preventing it from functioning normally. This, among other factors, means the cow cannot absorb the nutrition it needs and thus begins to lose body condition, milk production drops off, and diarrhea may occur. In effect, an animal with Johne’s disease is starving in spite of having a good appetite and eating well.

Sometimes, the malnutrition induced by the MAP infection causes low serum protein levels. Serum proteins help animals retain fluid within blood vessels, called oncotic pressure. When serum protein levels get too low, fluid leaks out into the surrounding tissues. In cattle, this is seen as submandibular edema – more commonly called “bottle jaw”, as in the Holstein cow pictured to the left.

Notice that this cow’s hair has been nicely clipped to make her look pretty. That’s because this particular cow had been in a major dairy cattle show. Johne’s disease is prevalent in both commercial and registered (purebred) dairy cattle worldwide.

How common is Johne's disease in dairy cattle?

Prevalence: an objective measure of rates of infection

The rates of MAP infection at one point in time is called infection prevalence. In animals, prevalence is typically reported in two ways: 1) at the cow-level, i.e. percentage of MAP-infected cows, and 2) at the herd-level, i.e. percentage of MAP-infected herds. Such surveys depend heavily on the accuracy of the test used and how the representative the animals or herd tested are of the general population. Epidemiologists report the actual percentage of animals or herds that test positive for MAP, called the apparent prevalence. They also use statistical methods to adjust for the accuracy of the test used in the survey to allow for a predicted number of false-negative and false-positive tests based on published estimates of test accuracy. This adjusted number is called the estimated true prevalence. EpiTools Epidemiological Calculator provides a tool for estimation of true prevalence.

With that information as background, let’s look at some survey data for different countries.

United States

The U.S. has surveyed the national dairy herd for Johne’s disease several times. The diagnostic methods used in each survey varied making direct comparisons difficult.

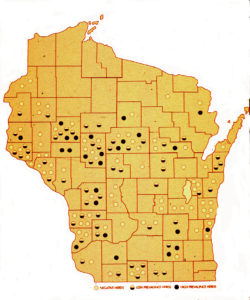

A U.S. national study in 1983-84 showed a 2.9% cow-level prevalence of infection in cull dairy cows, based on culture of ileocecal lymph nodes collected from culled dairy cows at slaughter (Merkal et al, 1987). A study by Whitlock et al in 1985 reported 7.2% infection rate among dairy cows and Collins et al. (1994) found that 4.8% of Wisconsin dairy cows were ELISA-positive and presumed MAP-infected (see map from the Wisconsin survey).

In 1996, the USDA:APHIS:VS agency known as the National Animal Health Monitoring System (NAHMS), conducted a survey in collaboration the livestock industry. The study was called the Dairy ‘96 Study. A total of 1,004 dairy producers voluntarily responded to the administered NAHMS Dairy ‘96 Study questionnaire and blood sampling. The data were weighted to represent dairy producers with at least 30 milk cows in the 20 sampled states, representing 79.4% of the U.S. dairy cow population. A total of 31,745 cows were tested using a commercial ELISA kit for Johne’s disease from 967 herds that did not vaccinate against Johne’s disease (vaccination can cause false-positive ELISA results).

The percentage of cows that tested ELISA-positive (apparent prevalence) was 2.5% with no significant differences among regions of the U.S. When adjusting for test accuracy (ELISAs have many false-negative results) they concluded that the estimated cow-level true prevalence was 3.4%. The epidemiologists used several techniques to determine the estimated true herd-level prevalence of MAP-infections and arrived at a figure of 21.6%.

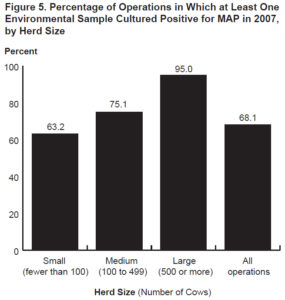

In 2007, another similar national survey was conducted but the diagnostic test used was culture of environmental fecal samples collected from multiple specific locations on the farm. The survey found that 68.1% of U.S. dairy herds were culture-positive for MAP and this translated to an estimated true herd-level MAP infection prevalence of 91.1% (Lombard, 2012). Additionally, they reported that herd-level prevalence was directly related to herd size: 63.2% of small herds (<100 cows) were MAP culture-positive infected while 95% of large herds (>500 cows were MAP culture-positive. This is likely because larger herds buy more cattle and buying cattle is the single biggest risk factor for herds to become MAP-infected.

Europe

Nielsen and Toft (2009) published a review of prior MAP infection prevalence estimates for multiple countries and multiple animal types. This review found that although a wide range of studies have been conducted, likely and comparable true prevalence estimates could rarely be calculated due to differences in study design and testing methodology. Based on a few studies where the reported prevalences appeared to be plausible, it was concluded that MAP infection prevalence estimates had to be a “best guess” rather than a precise estimate. Nonetheless, they stated that true MAP infection prevalence among cattle (cow-level) appeared to be approximately 20%. Herd-level prevalence guesstimates were >50%.

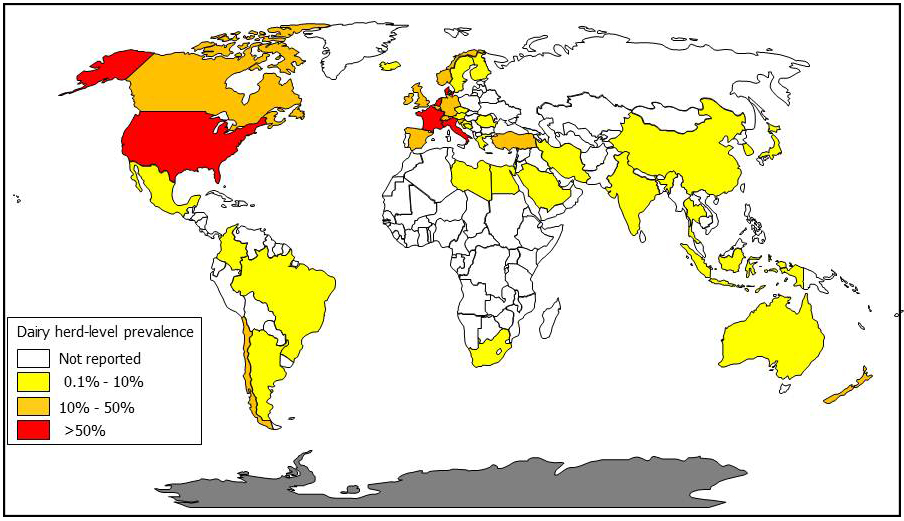

While specialists can quibble about the exact values for percentage of infected dairy cows and dairy herds, the inescapable conclusion is that MAP has become a common disease in virtually all countries with a significant dairy industry and the capacity to diagnose the infection.

The author of this website, Collins, has converted published survey results into dairy cow herd-level MAP infection prevalence estimates by country to create the map below (a MAP map).

What is the cost of Johne's disease to dairy producers?

Johne’s disease causes: 1) increased dairy cow cull rates, 2) decreased milk production, and 3) higher cow mortality rates. However, these economic losses are typically only significant in heavily infected herds. One of the more often cited economic studies was by Ott et al. (Preventive Veterinary Medicine 40:179-192, 1999). Using data from the NAHMS Dairy ’96 study, the authors reported that in heavily infected herds, defined as herds with >10% of cull cows showing clinical signs of Johne’s disease, the economic losses were over $200/cow. A portion of these losses were due to >700 Kg (1,540 lb.) lower milk production per cow. When averaged across all U.S. dairy herds the economic losses were estimated at US$22 to US$27 per cow equating to US$200-250 million annually. In 2016, the estimated annual cost to New Zealand from Johne’s disease in livestock was estimated at NZ$98 million (US$63.7 million).

These national cost estimates measured in the millions seems like a lot of money. But, like all things, it needs to be seen in perspective, i.e. in comparison to other diseases negatively impacting dairy farm economics.

Mastitis is widely regarded as the most expensive dairy cattle disease, Cornell researchers in 2016 estimated the cost of mastitis to the U.S. dairy industry at US$1.7 to US$2.0 billion. The cost per cow was estimated at US$117 to US$444. A 2018 Canadian study placed the cost of mastitis at CAD 662 (US$507) per cow, but this included both direct costs such as decreased milk production and indirect cost such as mastitist preventive measures (Aghamohammadi et al. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, May 2018).

The point is that Johne’s disease is not among the most costly diseases affecting dairy cattle. The net impact to a dairy herd depends primarily on the within-herd MAP infection prevalence. At low prevalence, e.g. <5% cattle testing ELISA-positive, the economic impact of the infection is likely to be less that the cost of infection control.

Each dairy herd is unique regarding the diseases it is working to control and farm’s economic capacity to deal with those infections. Consultation with the herd veterinarian is necessary to decide if MAP infection control is important and how best to invest in such a control program.

This presumes that Johne’s disease is only an animal health problem. Should MAP become recognized as a zoonotic human pathogen, public health issues would likely override animal production economics driving more aggressive control programs on dairy farms.

How do dairy cattle become infected?

Johne’s disease typically enters a herd or flock of animals when a MAP-infected, but healthy-looking, animal is purchased. This infected animal then sheds the organism onto the premises – perhaps onto pasture or into water shared by its new herdmates.

Young animals are far more susceptible to infection than are adults: these calves swallow the organism along MAP-contaminated milk, water or feed. Often, MAP-contaminated milk is collected from the infected but healthy-appearing animals. The milk may become contaminated from the environment (manure-stained teats) or, in the advanced stages of the infection, the bacterium is shed directly into the milk. Animals may even have been infected before they are born (called in utero transmission). Thus the infection spreads, often without the owner’s being aware of it.

How can you prevent your dairy herd from becoming infected?

Do not introduce it with purchased or leased animals! Try to purchase animals from a source herd free of Johne’s disease, based on whole-herd testing. Second best is to work with producer who knows the level of Johne’s disease in his or her herd and follows good infection control practices. Then, purchase test-negative animals from test-negative dams. Remember that Johne’s disease is a herd problem, and that knowing the test-status of numerous adults in the source herd will give you a much better sense of the risk of purchasing an infected animal than the one test result you might get on the one animal you wish to buy. Evaluating a source herd is not always easy but keeping the infection out of your herd is much less costly and troublesome than controlling it once it gets in. Laboratory tests are available for all animal species – you can even test fecal material collected from the environment nowadays.

Do not introduce it with purchased or leased animals! Try to purchase animals from a source herd free of Johne’s disease, based on whole-herd testing. Second best is to work with producer who knows the level of Johne’s disease in his or her herd and follows good infection control practices. Then, purchase test-negative animals from test-negative dams. Remember that Johne’s disease is a herd problem, and that knowing the test-status of numerous adults in the source herd will give you a much better sense of the risk of purchasing an infected animal than the one test result you might get on the one animal you wish to buy. Evaluating a source herd is not always easy but keeping the infection out of your herd is much less costly and troublesome than controlling it once it gets in. Laboratory tests are available for all animal species – you can even test fecal material collected from the environment nowadays.

How do you test cattle for Johne's disease?

New approaches are now available for testing that are cheaper and more reliable than ever before. There are two basic testing strategies: 1) detect MAP bacteria in fecal samples, or 2) detect an immune response (antibodies) to MAP using blood or milk samples. Detecting MAP directly is the more accurate, but also a more expensive, diagnostic method. MAP can be rapidly detected by a technology called PCR. Alternatively culture-methods can be used to grow MAP from fecal samples, a process taking 2-3 months. PCR and culture are equally accurate.

The serum portion of blood samples or milk samples are used to detect antibodies to MAP using technology called ELISA. There are several commercial ELISA kits for Johne’s disease. ELISAs have much lower diagnostic sensitivity (ability to detect MAP-infected animals) compared to methods for detecting MAP bacteria in fecal samples. ELISAs typically have a diagnostic specificity of roughly 99.5%, meaning false-positive results can occur, but infrequently. For this reason, ELISAs are considered “screening tests” and under most circumstances should be followed up with a confirmatory test, i.e. MAP detection test. The lower cost of ELISAs makes them a popular test.

MAP detection methods can be done on “pooled” samples. This involves submission of fecal samples from individual animals. The laboratory then mixes equal amounts of feces from 5 animals and then does a single test on that pool. If the pool is test-positive, then the fecal samples used for that pool are tested individually.

This can significantly decreasing the cost per animal tested in a herd but is only appropriate for herds that are either not MAP-infected (surveillance testing) or are infected at a low prevalence (percentage of animals infected in the herd or flock).

More details on diagnostic testing can be found by selecting an dairy cattle in the menu bar and then topic “Diagnosis” on the right-hand menu. Consult with your veterinarian to select the best approach for your animals and situation. You can also select “Testing Services” in the menu bar to be directly connected to the Johne’s disease testing information provided by the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory.

How do you control Johne's disease?

Specific methods for MAP infection control depend on the animal species, the resources available, the goals of the animal enterprise, and the methods of animal husbandry. All control approaches however rely on two core strategies that must be employed at the same time:

- Newborn animals must be protected from infection by being born and raised in a clean environment and fed milk and water free of MAP contamination. The primary source of MAP contamination is manure from an infected adult animal.

- Adult animals infected with MAP must be identified using laboratory tests and culled or managed to ensure no young animals are exposed to their milk or manure.

Can Johne's disease be cured?

No. In the few studies that attempted to treat Johne’s disease with antibiotics, symptoms appeared to subside but animals relapsed after therapy was halted. As with other mycobacterial infections (for instance, human tuberculosis) multiple antibiotics must be injected or given orally daily for months. For most animals, this is cost-prohibitive as well as not feasible. For more detailed information visit the page on “Antimicrobial Therapy”.

Can humans get Johne's disease?

The term “Johne’s disease” is used only to describe the clinical illness in ruminants that occurs after MAP infection.

There is a human ailment however called “Crohn’s disease” that in many ways resembles Johne’s disease. Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that has no known cause and no known cure. The consensus of several studies is that MAP is consistently “associated” with Crohn’s disease patients as compared to controls. Whether that association is causal or coincidental remains unknown. Some researchers believe MAP is the cause of Crohn’s disease for at least a subset of patients and multiple reports describe clinical improvement of Crohn’s disease patients using anti-MAP antibiotics. The majority of gastroenterologists, however, believe that MAP, if found in patients, is simply a by-stander amongst the many other organisms that are found in an inflamed, malfunctioning gastrointestinal tract. No connection has been shown between contact with animals having Johne’s disease or dairy product consumption and Crohn’s disease. This aspect of MAP is a complex and controversial area of scientific investigation.

A detailed discussion of this topic can be found in “Zoonotic Potential” on this website.