This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

What is Johne's disease and what causes it?

Johne’s (pronounced “Yoh-nees”) disease and paratuberculosis are two names for the same animal disease. Named after a German veterinarian, this fatal gastrointestinal disease was first clearly described in a dairy cow in 1895.

A bacterium named Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (abbreviated “MAP”) is the cause of Johne’s disease. The infection happens in the first few months of a lamb’s life but the animal may stay healthy for a very long time. Symptoms of disease may not show up for many months to years after the infection starts. This period of time is called the “incubation period”. MAP infections are contagious, which means it can spread from one sheep to another, and from one species to another (cows to sheep, sheep to goats, etc.), depending on the strain of MAP involved. S-strains of MAP are less likely to transmit to other animals than are C-strains, also called cattle strains.

MAP is very hardy – while it cannot replicate outside of an infected animal, it is resistant to heat, cold and drying. See “Biology of MAP” for more information about this bacterial pathogen.

What kind of animals get Johne's disease?

Johne’s disease is primarily a health problem for ruminant species (ruminants are hoofed mammals that chew their cud and have a 3-4 chambered stomach) and occurs most frequently in domestic agriculture herds. Some of the more common ruminants are cattle, sheep, goats, deer, and bison. It is particularly common in dairy cattle, not because they are more susceptible to infection but because they are more frequently exposed to the organism that causes Johne’s disease (MAP). Infected ruminants have been reported from all parts of the world. Non-ruminants such as omnivores or carnivores (birds, raccoons, fox, mice, etc.) may become infected, but rarely do they become sick because of the infection.

What are the clinical signs of Johne's disease and what causes them?

Weight loss in sheep with a good appetite is the main clinical sign of Johne’s disease. Diarrhea is far less common than in cattle with Johne’s disease. The MAP infection occurs in lambs in the first months of life, but signs of disease usually do not appear until the animals are adults. Despite continuing to eat well, adult sheep become emaciated and weak. Since the signs of Johne’s disease are similar to those for several other diseases, laboratory tests are needed to confirm a diagnosis. If a case of Johne’s disease occurs, it is very likely that other MAP-infected sheep, that may still appear healthy but are incubating the infection, are in the herd.

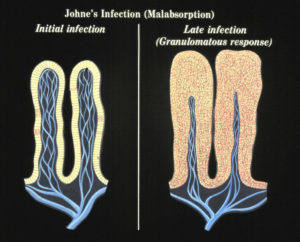

No one fully understands what causes a clinically normal sheep that has been infected by MAP for months or years to suddenly become sick from the infection. The MAP infection resides primarily in the intestinal wall and the animal responds to the infection by sending white blood cells to this site. The result is a thickened intestinal wall causing a failure to absorb nutrients. While this logically explains why sheep become “unthrifty”, there are likely other factors related to the MAP bacteria and the sheep’s response to this infection that are involved. Weight loss is a common feature of other mycobacterial infections as well.

While weight loss is always present in clinical cases of Johne’s disease, a range of other clinical signs can also occur such as, wool break, bottle jaw (without severe anemia) and general weakness.

Bottle jaw is the results of malnutrition induced by the MAP infection which leads to low serum protein levels. Serum proteins help animals retain fluid within blood vessels, called oncotic pressure. When serum protein levels get too low, fluid leaks out into the surrounding tissues, called edema. When this edema happens under the jaw it is called submandibular edema – more commonly called “bottle jaw”, as in the sheep pictured to the left. Parasites can also cause bottle jaw and should be ruled out before testing for Johne’s disease.

Bottle jaw is the results of malnutrition induced by the MAP infection which leads to low serum protein levels. Serum proteins help animals retain fluid within blood vessels, called oncotic pressure. When serum protein levels get too low, fluid leaks out into the surrounding tissues, called edema. When this edema happens under the jaw it is called submandibular edema – more commonly called “bottle jaw”, as in the sheep pictured to the left. Parasites can also cause bottle jaw and should be ruled out before testing for Johne’s disease.

For more images of sheep with clinical Johne’s disease visit this page of our website.

How common is Johne's disease?

Every country that has tested their ruminant domestic agriculture species for Johne’s disease has found cases of infection. No surveys have been done in the U.S. but USDA reports that 16% of the national sheep flock is culled annually and over 10% of these culled sheep have weight loss but a good appetite. MAP could well be the cause of many of these culls.

Australia has the most experience with Johne’s disease in sheep, called ovine Johne’s disease (OJD). The Australian websites about OJD are filled with useful information.

How do sheep become infected?

Johne’s disease typically enters a flock when a MAP-infected, but healthy-looking, animal is purchased. This infected sheep then sheds MAP in its feces onto the premises – perhaps onto pasture or into water shared by its new herdmates. Young lambs are far more susceptible to infection than are adults: these lambs swallow the organism along with grass or water. In the advanced stages of the infection, the bacterium is shed directly into the milk. Animals may even have been infected before they are born, called in utero transmission, if the ewe is in advanced stages of the MAP infection. Thus the infection spreads insidiously, without the owner’s being aware of it.

How dan you protect your flock from Johne's disease?

Do not introduce it!

Try to purchase animals from a source herd free of Johne’s disease. Second best is to work with producer who knows the level of Johne’s disease in his or her herd, follows good infection control practices, and then purchase test-negative lambs born to test-negative ewe. Remember that Johne’s disease is a flock problem, and that knowing the test-status of numerous adult sheep in the source flock will give you a much better sense of the risk of purchasing an infected animal than the one test result you might get on the single sheep you wish to buy. Evaluating a source herd is not always easy but keeping the infection out of your herd is much less costly and troublesome than controlling it once it gets into a herd. The PCR for MAP on fecal samples is by far the best available diagnostic test.

After a new animal comes to your farm, it is advisable to repeat diagnostic tests while the animal is held in quarantine – safely separated from the rest of the herd.

How do you test sheep for Johne's disease?

For sheep, there is really only one “best test”, PCR for MAP detection on fecal samples. The blood test for Johne’s disease (ELISA) has very low sensitivity in sheep. Culture methods can detect the C-strain but growth of the S-strain is much more difficult and takes much longer. Pooling of samples (by the diagnostic laboratory) can help make PCR testing more affordable.

How do you control Johne's disease in sheep flocks?

The best methods for MAP infection control in your sheep flock depend on the resources available, the goals of your enterprise, and the methods you use to take care of your sheep. All control methods however rely on two core strategies that must be employed at the same time:

Lambs must be protected from infection by being born and raised in a clean environment and fed milk and water free of MAP contamination. The primary sources of MAP contamination are manure and/or milk from infected adult animals.

Adult sheep infected with MAP must be identified and culled managed to ensure no lambs are exposed to their milk or manure.

No vaccines are available in the United States for Johne’s disease in sheep, however, in Spain, Australia and several other countries vaccines are used. This vaccine does not fully block MAP infections but it does keep extend the life of infected sheep and keep them profitable longer. For more information about vaccination of sheep readers should visit the Australian OJD website.

Can Johne's disease in sheep be cured with antibiotics?

No. In the few studies that attempted to treat Johne’s disease with antibiotics in cattle, symptoms appeared to subside but animals relapsed after therapy was halted. As with other mycobacterial infections (for instance, human tuberculosis) multiple antibiotics must be injected or given orally daily for months. For most animals, this is cost-prohibitive as well as infeasible. For more detailed information visit the page on “Antimicrobial Therapy”.

Can humans get Johne's disease?

The term “Johne’s disease” is used only to describe the clinical illness in ruminants that occurs after MAP infection.

There is a human ailment however called “Crohn’s disease” that in several ways resembles Johne’s disease. Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that has no known cause and no known cure. In some studies MAP has been found in tissues of Crohn’s disease patients more often than controls. Some researchers believe MAP contributes to Crohn’s disease for at least a subset of patients. The majority of gastroenterologists, however, do not; they believe that MAP, if found in this subset of patients, is simply a by-stander amongst the many other organisms that are found in a malfunctioning gastrointestinal tract. No connection has been shown between contact with animals with Johne’s disease, dairy product or meat consumption and Crohn’s disease. This aspect of MAP is a complex and controversial area of scientific investigation. A detailed discussion of this topic can be found on the “Zoonotic Potential” page of this website.