Mortier & colleagues from the Department of Production Animal Health, University of Calgary in Canada conducted a trial to evaluate the effect of calf age at the time of MAP exposure and dose of MAP ingested on the rate of infection progression. This publication appeared in 2014 but is so helpful in understating the epidemiology and pathogenesis of MAP infections in dairy calves it is being highlighted in today’s news positive. This Open Access article appears in the journal Veterinary Research.

Abstract

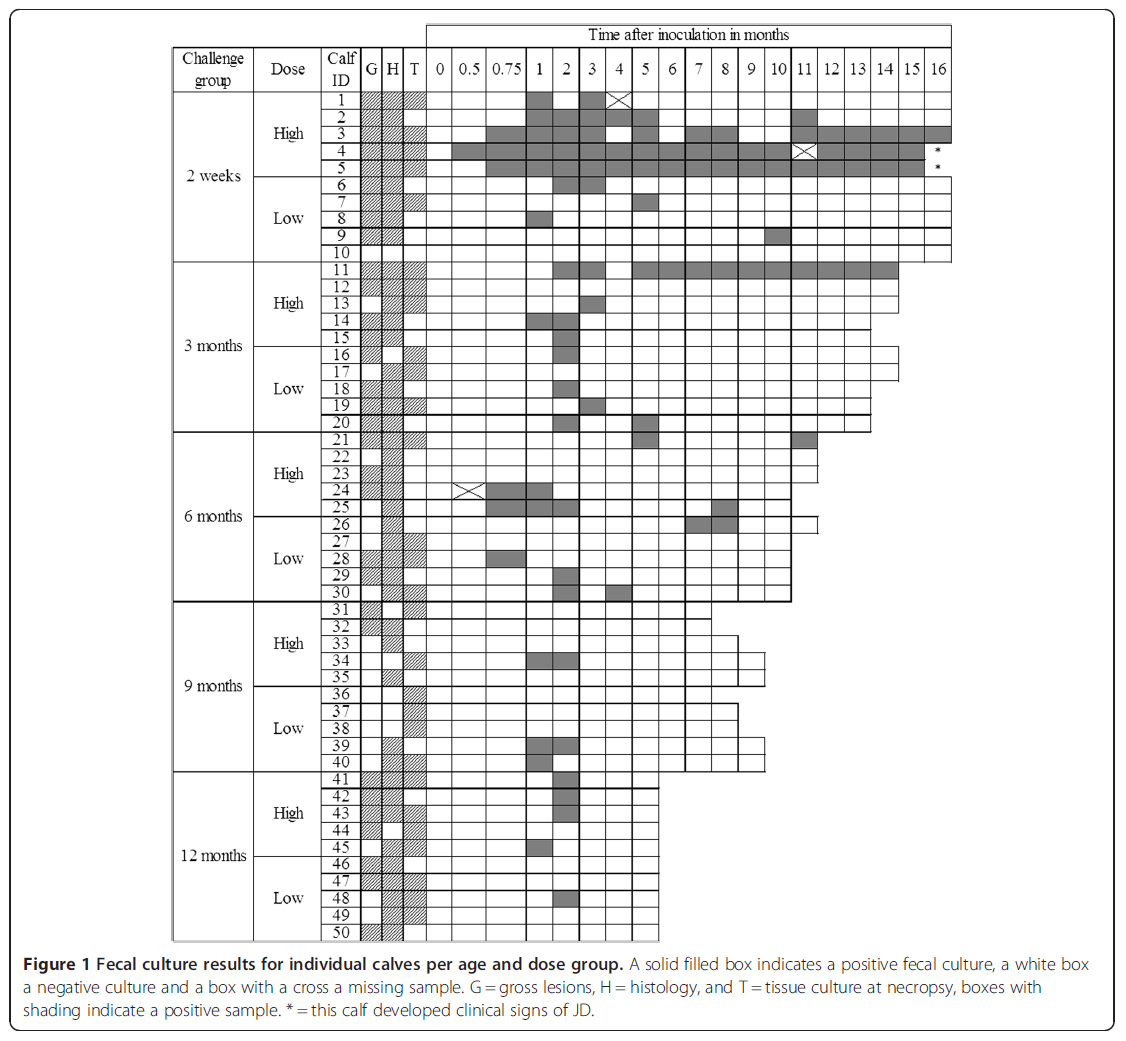

Although substantial fecal shedding is expected to start years after initial infection with Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP), the potential for shedding by calves and therefore calf-to-calf transmission is underestimated in current Johne’s disease (JD) control programs. Shedding patterns were determined in this study in experimentally infected calves. Fifty calves were challenged at 2 weeks or at 3, 6, 9 or 12 months of age (6 calves served as a control group). In each age group, 5 calves were inoculated with a low and 5 with a high dose of MAP. Fecal culture was performed monthly until necropsy at 17 months of age. Overall, 61% of inoculated calves, representing all age and dose groups, shed MAP in their feces at least once during the follow-up period. Although most calves shed sporadically, 4 calves in the 2-week and 3-month high dose groups shed at every sampling. In general, shedding peaked 2 months after inoculation. Calves inoculated at 2 weeks or 3 months with a high dose of MAP shed more frequently than those inoculated with a low dose. Calves shedding frequently had more culture-positive tissue locations and more severe gross and histological lesions at necropsy. In conclusion, calves inoculated up to 1 year of age shed MAP in their feces shortly after inoculation. Consequently, there is potential for MAP transfer between calves (especially if they are group housed) and therefore, JD control programs should consider young calves as a source of infection.

Comment: Since calves shed MAP in feces soon after infection, it’s possible that they can transmit the infection to other calves that they are in contact with. Rather than change management practices to limit calf to calf contact, it seems more rational to invest efforts to prevent calves from becoming MAP-infected in the first place. This is done by: 1) testing the adult herd regularly, 2) culling or isolating infected cows, 3) calving test-negative cows in clean maternity pens, 4) promptly removing calves from cows, and 5) insuring colostrum fed to calves is collected only from test-negative cows and that it is collected with utmost care to avoid fecal contamination.