One-hundred eighty-three years ago, on December 10, 1839, Heinrich Albert Johne was born in Dresden, Germany. It seems fitting that Johnes.org celebrate, on this date, his lasting contribution to veterinary medicine.

One-hundred eighty-three years ago, on December 10, 1839, Heinrich Albert Johne was born in Dresden, Germany. It seems fitting that Johnes.org celebrate, on this date, his lasting contribution to veterinary medicine.

Below you will find the story of his discovery, a brief biography, a little about the pathogen name, and the story of how I found this photo.

How it all started.

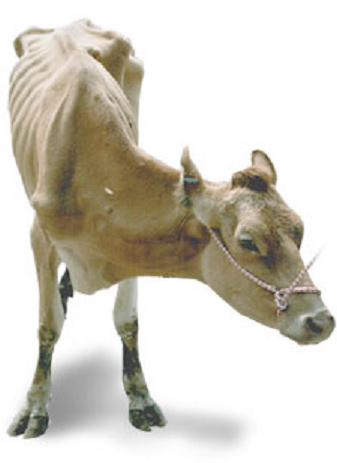

Dr. F. Harmes, a veterinarian in the Oldenburg region of Germany in 1895, had a client with a Guernsey cow that was doing poorly. Dr. Harmes’ preliminary diagnosis was intestinal tuberculosis (TB). TB in cattle was quite common in Germany then. But when he did the tuberculin skin test to confirm his diagnosis, the cow tested negative. So, the reason for the cow’s condition remained a mystery.

Dr. F. Harmes, a veterinarian in the Oldenburg region of Germany in 1895, had a client with a Guernsey cow that was doing poorly. Dr. Harmes’ preliminary diagnosis was intestinal tuberculosis (TB). TB in cattle was quite common in Germany then. But when he did the tuberculin skin test to confirm his diagnosis, the cow tested negative. So, the reason for the cow’s condition remained a mystery.

A few months later, the cow died. Curious as to what killed the cow, Dr. Harmes sent intestines and other tissues to the Pathology Unit at the veterinary school in Dresden. There the tissues were examined by Dr. Heinrich A. Johne, Professor of Pathology, and Dr. Langdon Frothingham, a visiting scientist from the Pathology Unit in Boston, Massachusetts.

They observed that the small intestine was quite a bit thicker than expected and that lymph nodes near this thick intestine were enlarged. The photo at the right shows a normal intestine at the top and the intestine thickened due to Johne’s disease at the bottom. Lymphoid tissue, called Peyer’s Patches, are also quite prominent (the raised and slightly red tissue running long-ways down the center of the thickened intestine). Interestingly, Dalziel in 1913 saw the same kind of pathology when he removed a section of intestine from a person with Crohn’s disease remarking in his report that it resembled the cattle problem Dr. Johne had described.

They observed that the small intestine was quite a bit thicker than expected and that lymph nodes near this thick intestine were enlarged. The photo at the right shows a normal intestine at the top and the intestine thickened due to Johne’s disease at the bottom. Lymphoid tissue, called Peyer’s Patches, are also quite prominent (the raised and slightly red tissue running long-ways down the center of the thickened intestine). Interestingly, Dalziel in 1913 saw the same kind of pathology when he removed a section of intestine from a person with Crohn’s disease remarking in his report that it resembled the cattle problem Dr. Johne had described.

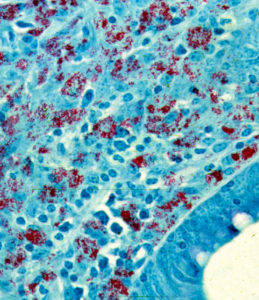

Using what at the time were newly developed histopathology techniques, parts of the intestine were “fixed” (pickled in formaldehyde), sliced into very thin sections, placed on a microscope slide, and stained with special dyes – known as an acid-fast stain – designed to help visualize bacteria of the type causing TB.

Under the microscope, Drs. Johne and Frothingham saw that the intestinal wall was filled with inflammatory cells of the kind to be expected in TB (macrophages and lymphocytes – the blue-colored stuff in the photo). In addition, they saw abundant red-staining bacteria (which microbiologists call acid-fast bacteria) throughout the inflamed tissues. Basically, it looked just like intestinal TB. But, when a sample of the fresh infected tissue containing the red-staining bacteria was injected into guinea pigs, it didn’t cause TB. This took place shortly after Louis Pasteur had devised the “germ theory” of disease and before techniques for growing bacteria in the laboratory were widely available. Inoculating animals, therefore, was a routine way of detecting infectious microbes such as those that cause TB, and guinea pigs are quite susceptible to tuberculosis. So, the diagnosis on this cow remained a mystery.

Drs. Johne and Frothingham concluded that the disease seen in the very sick Guernsey cow was caused by a bacterium other than the one normally causing TB in cattle, namely Mycobacterium bovis. They speculated that perhaps the pathology was due to a related bacterial pathogen such as the one causing TB in birds, aptly named Mycobacterium avium. Considering their subject’s gross pathology, microscopic pathology (histopathology) and animal inoculation findings, they proposed the name “pseudotuberculous enteritis” for the disease; a designation meaning inflammation of the intestine resembling intestinal TB but not actually the same as intestinal TB – somehow different. Soon after publication of their report, veterinarians began reporting outbreaks of this curious intestinal malady among dairy cows in Denmark, The Netherlands and elsewhere in continental Europe.

More on Dr. Johne.

H.A. Johne was the son of a veterinarian. Twenty years later, he became a veterinarian himself and held a practice for the next seven years. From 1866-1876, he acted as district veterinary inspector. He was then appointed to a lectureship at the veterinary school in Dresden. For a teacher of veterinary medicine, he lectured in an unusually wide range of subjects: embryology, histology, obstetrics, exterior, physical diagnostics. In 1879, he was appointed professor of pathological anatomy and of general pathology. Later he also lectured on parasitology and methodical zoology, and he also started classes in such a new branch of research as bacteriology.

As a scientist, he concerned himself with tuberculosis, anthrax, rabies, glanders, actinomycosis, bothryomycosis among others. As a writer he left a wide literary production. His books were printed in a dozen editions. For many years he also edited “Zeitschrift tor Tiermedizin”, and acted as co-editor of “Rundschau auf dem Gebiet der Fleischbeschau”. In 1887, he visited Denmark, where he was nominated honorary member of the Danish Association of Veterinarians and decorated with the Order of Knight of the Dannebrog.

He was often guest of Professor B. Bang and his family, the flat of Bangs’ is today the Veterinary History Museum, established in 1973 at the Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University in Copenhagen. His motto was: Duty Above All. With the distinguished array of titles: Geheim-Medizinalrat, Professor, Dr. med., Dr. med.vet.h.c. and Dr. phil., Heinrich Albert Johne retired in 1904, respected and honored by his many students and by foreign veterinary schools and societies. He died in 1910.

MAP

In 1912, in one of those curious discoveries by serendipity, Twort and Ingram discovered how to grow the cause of Johne’s disease in the laboratory and named this bacterial pathogen Mycobacterium enteritidis chronicae pseudotuberculosae bovis johne. Time and technology led to name changes and the cause of Johne’s disease is today known as Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis or simply MAP. Johne’s disease, also called paratuberculosis, is now a disease of major global importance.

Dr. Johne photo credit

I found the photo of Dr. Johne was hanging in halls of the State Veterinary Serum Institute when I was on sabbatical working with Dr. J.B. Jørgensen at the State Veterinary Serum Laboratory, Copenhagen, Denmark. Together we were comparing new methods for culturing MAP from clinical samples. On my departure, Dr. Jørgensen gifted me a copy of this photo which hangs in my office and also appears on the Wikipedia page about Dr. Johne.

PS

For more historical events and people important to understanding of Johne’s disease visit our history timeline.