COST OF JD TO THE DAIRY INDUSTRY

2021-02-18 16:10:38Philip Rasmussen from the Department of Ecosystem and Public Health, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, and colleagues have published a study on the economic losses due to Johne’s disease in dairy cattle. Their Open Access article was published online in the Journal of Dairy Science January 14, 2021.

ABSTRACT

Johne's disease (JD), or paratuberculosis, is an infectious inflammatory disorder of the intestines primarily associated with domestic and wild ruminants including dairy cattle. The disease, caused by an infection with Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) bacteria, burdens both animals and producers through reduced milk production, premature culling, and reduced salvage values among MAP-infected animals. The economic losses associated with these burdens have been measured before, but not across a comprehensive selection of major dairy-producing regions within a single methodological framework. This study uses a Markov chain Monte Carlo approach to estimate the annual losses per cow within MAP-infected herds and the total regional losses due to JD by simulating the spread and economic impact of the disease with region-specific economic variables. It was estimated that approximately 1% of gross milk revenue, equivalent to US$33 per cow, is lost annually in MAP-infected dairy herds, with those losses primarily driven by reduced production and being higher in regions characterized by above-average farm-gate milk prices and production per cow. An estimated US$198 million is lost due to JD in dairy cattle in the United States annually, US$75 million in Germany, US$56 million in France, US$54 million in New Zealand, and between US$17 million and US$28 million in Canada, one of the smallest dairy-producing regions modeled.

COMMENT

This paper is informative, international in scope, and has an excellent list of references that backup the cost estimates used in this economic modelling exercise.

JD IN DAIRY CATTLE LECTURES

2021-02-12 01:00:52Dairy producers and their herd veterinarians commonly ask:

- What is the best test to help control JD in dairy cattle?

- What should I do with cattle that test ELISA-positive?

- How can I avoid buying MAP-infected cattle?

- Which test should I use to certify my herd is free of Johne’s disease?

- What are my first steps in controlling Johne’s disease?

- Should I use the ELISA for JD on blood (serum) or milk samples?

- Will JD control improve my farm profitability - what's the evidence?

- How common are national JD control programs and how to they work?

These and many more questions are addressed in a new two-part lecture series titled “Johne’s Disease in Dairy Cattle part 1 and part 2” (40 minutes each) now available on this website. You will also find on this same web page lectures titled “Johne’s Disease in Goats” and “MAP is a Zoonotic Pathogen”.

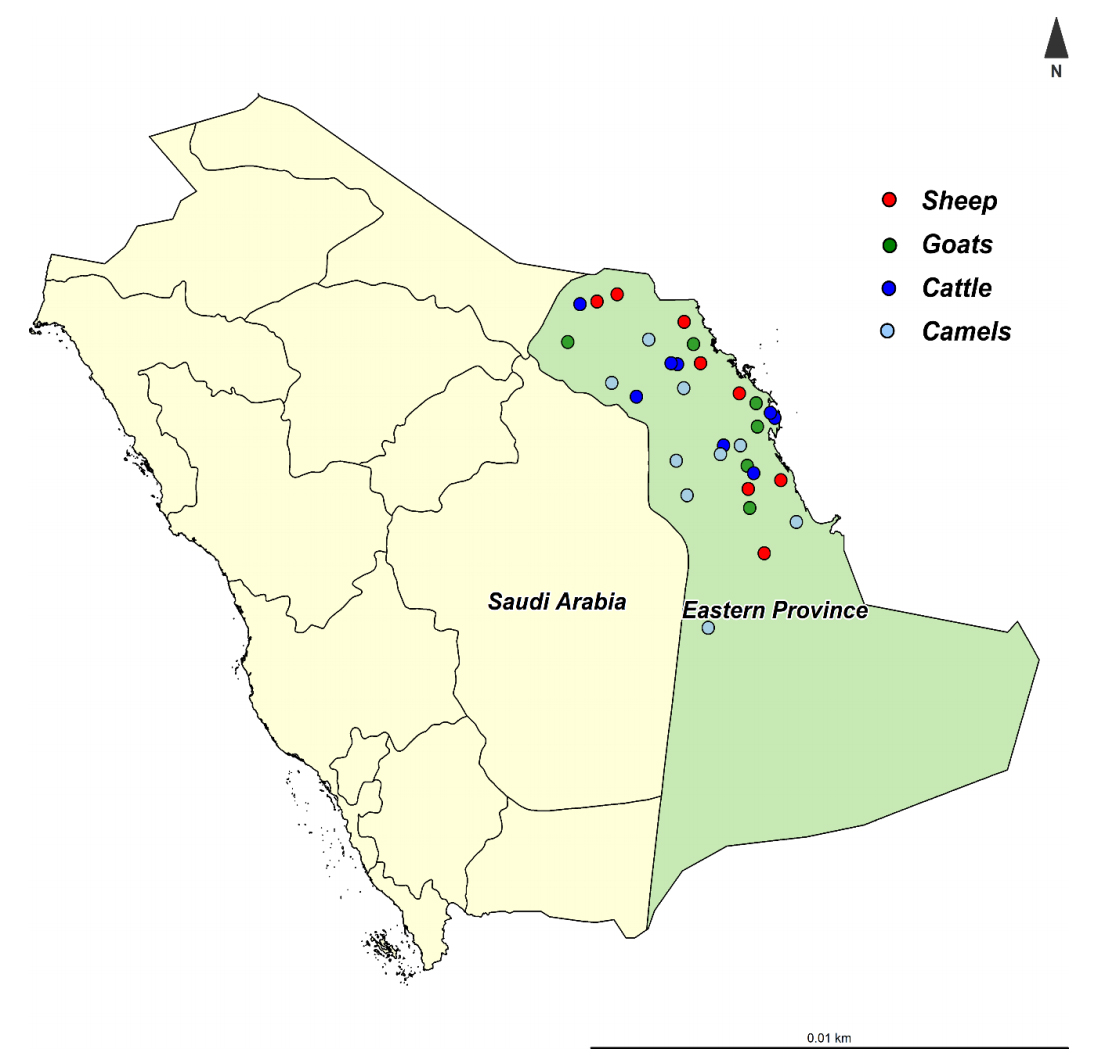

JOHNE’S DISEASE IN SAUDI ARABIA

2021-02-06 01:00:06 An international team of researchers, led by Ibrahim Elsohaby, tested 31 herds of animals with prior histories of Johne’s disease in the Eastern Province in Saudi Arabia. The Eastern Province is the third most populous province in Saudi Arabia, with varying climatic conditions from semi-desert to desert. The Eastern Province shares the borders with five countries (Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates), which may increase the risk of pathogen introduction to the country.

An international team of researchers, led by Ibrahim Elsohaby, tested 31 herds of animals with prior histories of Johne’s disease in the Eastern Province in Saudi Arabia. The Eastern Province is the third most populous province in Saudi Arabia, with varying climatic conditions from semi-desert to desert. The Eastern Province shares the borders with five countries (Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates), which may increase the risk of pathogen introduction to the country.

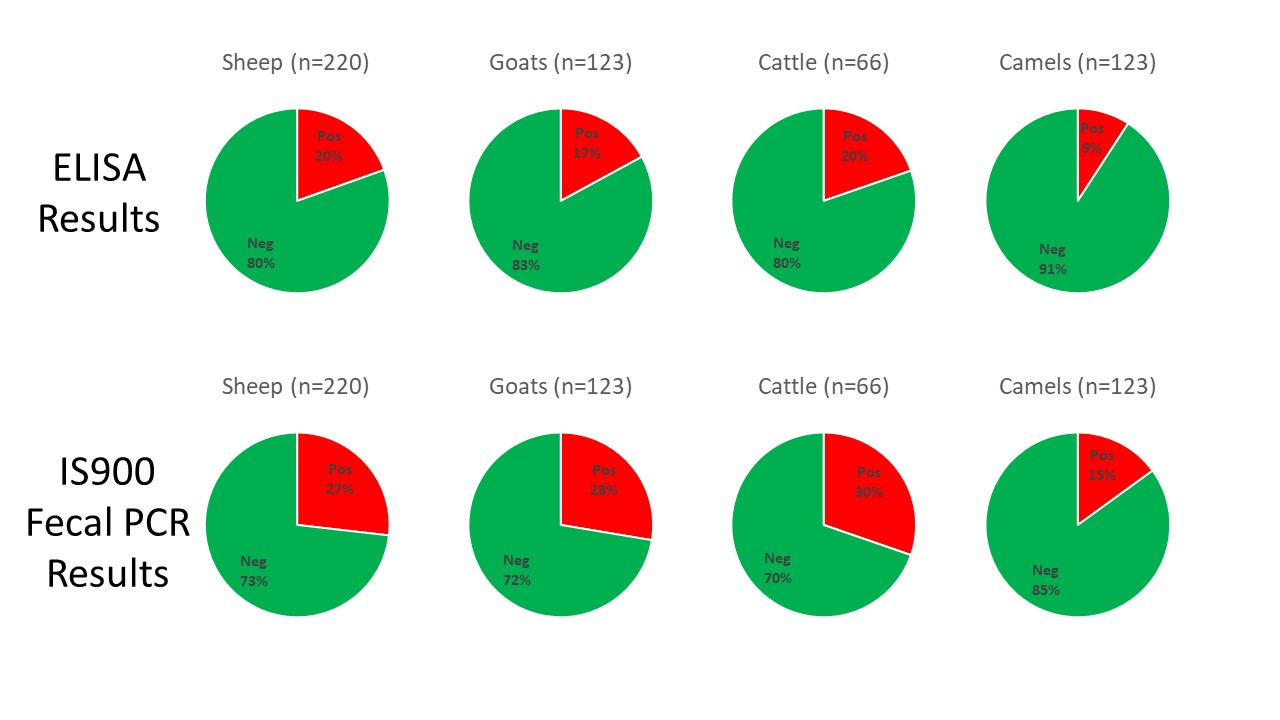

A total of 649 sheep, goats, cattle, and camels were tested by ELISA on serum samples and IS900 PCR on fecal samples. The study was reported this month in the journal Animals. The pie charts below were created to summarize the study findings. They reveal high infection rates among all four animals species and the higher diagnostic sensitivity of fecal PCR as compared to serum ELISAs. Interestingly, the S (sheep)-strain of MAP was more prevalent than the C (cattle)-strain.

Abstract

The objectives of the present study were to characterize Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis (MAP) infection using serological and molecular tools and investigate the distribution and molecular characterization of MAP strains (cattle (C) and sheep (S) types) in sheep, goat, cattle, and camel herds in Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. Serum and fecal samples were collected from all animals aged >2 years old in 31 herds (sheep = 8, goats = 6, cattle = 8 and camels = 9) from January to December 2019. Serum samples were tested by ELISA for the detection of MAP antibodies. Fecal samples were tested by PCR for the detection of MAP IS900 gene and the identification of MAP strains. MAP antibodies were detected in 19 (61.3%) herds. At the animal level, antibodies against MAP were detected in 43 (19.5%) sheep, 21 (17.1%) goats, 13 (19.7%) cattle and 22 (9.1%) camels. The IS900 gene of MAP was detected in 23 (74.2%) herds and was directly amplified from fecal samples of 59 (26.8%) sheep, 34 (27.6%) goats, 20 (30.3%) cattle and 36 (15.0%) camels. The S-type was the most prevalent MAP type identified in 15 herds, and all were identified as type-I, while the C-type was identified in only 8 herds. The IS900 sequences revealed genetic differences among the MAP isolates recovered from sheep, goats, cattle and camels. Results from the present study show that MAP was prevalent and confirm the distribution of different MAP strains in sheep, goat, cattle and camel herds in Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia.

This graphic from the publication shows an example of Johne's disease in goats.

Comment

Few reports on paratuberculosis in Saudi Arabia are available making this an important addition to the body of evidence that Johne’s disease is a global problem.

JOHNE’S DISEASE IN GOATS

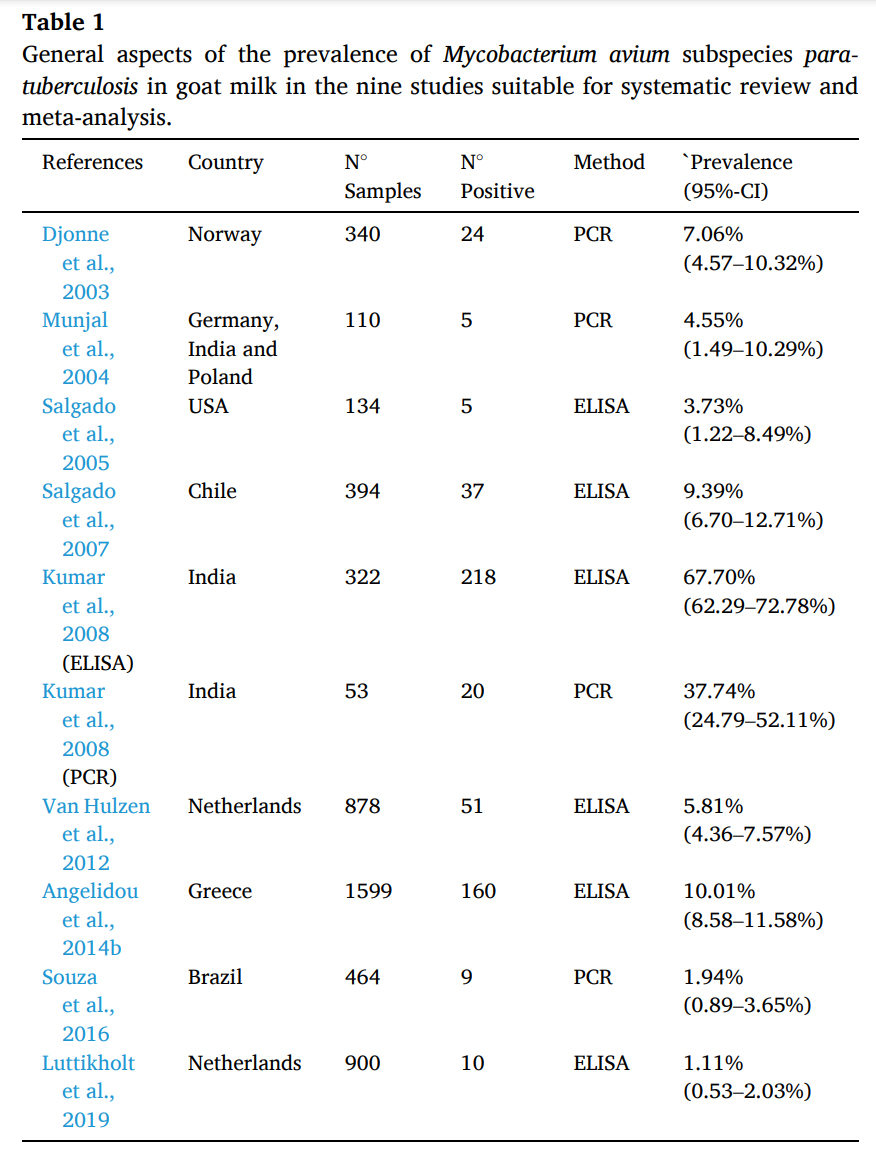

2021-01-28 01:00:46 João Paulo de Lacerda Roberto and 8 colleagues from the Federal University of Campina Grande, Post-Graduate Program in Animal Science and Health, Patos, PB, Brazil conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on scientific articles concerning MAP in goats. They specifically examined reports on detection of antibody to MAP in goat milk and detection of MAP in goat milk by PCR methods. They found wide ranging herd-level prevalence estimates among countries as shown in their table below.

João Paulo de Lacerda Roberto and 8 colleagues from the Federal University of Campina Grande, Post-Graduate Program in Animal Science and Health, Patos, PB, Brazil conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on scientific articles concerning MAP in goats. They specifically examined reports on detection of antibody to MAP in goat milk and detection of MAP in goat milk by PCR methods. They found wide ranging herd-level prevalence estimates among countries as shown in their table below.

Abstract

Paratuberculosis is an incurable infectious disease that affects several species, including goat (Capra hircus). The etiologic agent is Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) that has tropism for the intestine, causing anorexia, progressive weight loss and death. In goats, the main transmission route is the ingestion of water and food contaminated by infected feces. Affected animals also eliminate the agent through milk, with a potential biological risk to public health. Thus, the aim of this study was to conduct a research of the literature available in electronic media for a systematic review, followed by a meta-analysis of the results found on prevalence and diagnostic tests adopted in the detection of MAP antibodies and DNA in goat milk. The following search parameters were used: “Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis” AND (goat OR small ruminant) AND (milk OR pasteurized milk). Strictly obeying pre-established criteria, 437 articles were selected from the respective electronic databases of scientific content: ScienceDirect (285), PubMed (68), Web of Science (60) and Scopus (24), of which nine papers were elected to the construction of the systematic review and meta-analysis. The prevalence of MAP antibodies in milk detected by milk-ELISA ranged from 1.1 to 67.7% and the prevalence of MAP DNA in goat milk detected by MAP-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) ranged from 1.94 to 37.74%. A meta-analysis indicated a combined MAP infection prevalence of 8.24%, but with high heterogeneity among study findings (I2 = 98.7%). The identification of the MAP in goat milk implies the need for surveillance of the agent in order to prevent economic losses and impact on public health.

Comment

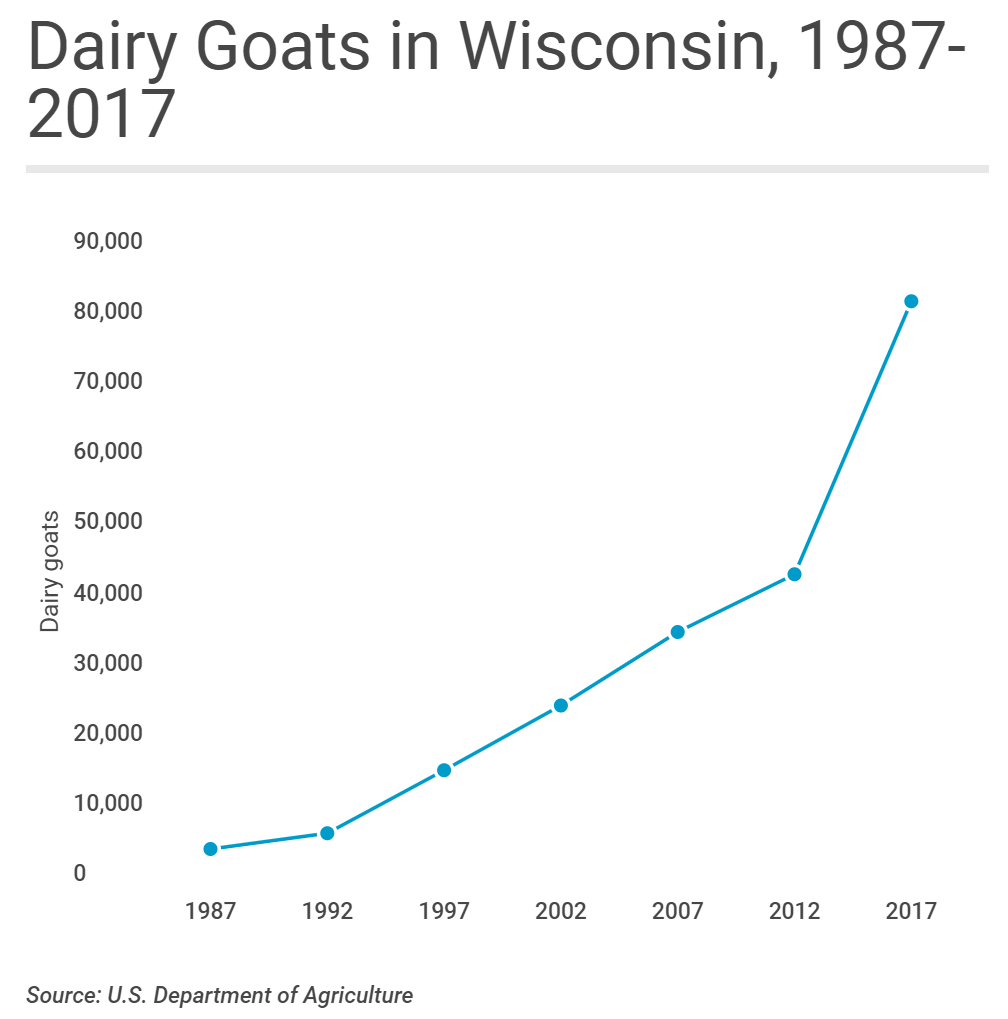

The problem of Johne’s disease in goats has been overlooked for far too long. In Wisconsin, as in many places in the world, the goat industry is growing, particularly for dairy goats. Data from the United States Department of Agriculture, which counts livestock across the United States every 5 years, show just how much Wisconsin dominates the nation's dairy goat industry. In 2017, the most recent year the USDA surveyed producers, the size of Wisconsin's dairy goat herd easily topped the nation at more than 83,000-head. California came in a distant second, with some 43,000 dairy goats, while Iowa, Texas and Missouri rounded out the top five.

It's not only the sheer size of Wisconsin's dairy goat herd that stands out: The state also leads the nation in the value of sales from dairy goat operations and is the epicenter of national growth in goat dairy. The problem is that rapid goat herd expansion brings with it a high risk of introducing Johne’s disease and once this chronic infection takes root in a herd it becomes a financial drain on the business and a major risk to product sales should MAP become widely recognized as a food-borne zoonotic pathogen.

JD CONTROL ON GRAZING DAIRY FARMS

2021-01-21 17:59:21 F. Biemans from the Centre for Veterinary Epidemiology and Risk Analysis, UCD School of Veterinary Medicine, University College Dublin, Ireland together with colleagues from INRAE, Oniris, BIOEPAR, Nantes, France and Teagasc, Oak Park, Carlow, Ireland, published a study titled: Modelling transmission and control of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis within Irish dairy herds with compact spring calving. Their article appears in the January 2021 issue of Preventive Veterinary Medicine.

F. Biemans from the Centre for Veterinary Epidemiology and Risk Analysis, UCD School of Veterinary Medicine, University College Dublin, Ireland together with colleagues from INRAE, Oniris, BIOEPAR, Nantes, France and Teagasc, Oak Park, Carlow, Ireland, published a study titled: Modelling transmission and control of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis within Irish dairy herds with compact spring calving. Their article appears in the January 2021 issue of Preventive Veterinary Medicine.

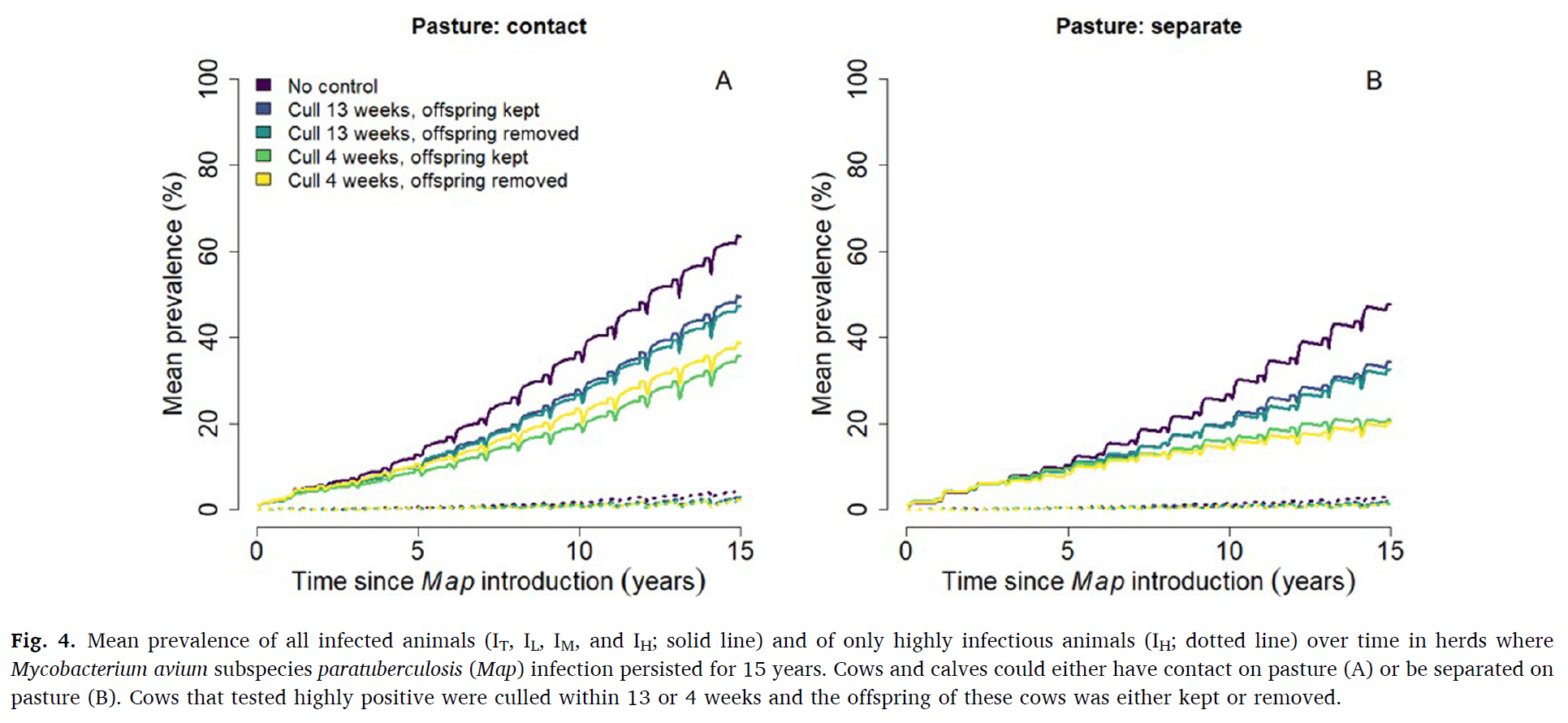

This graphic from their publication shows the spread of Johne's disease in grazing dairy herds with and without appropriate control measures. Annual testing by serum ELISA, prompt culling of the high (strong) ELISA-positive cows and separation of the calf from the cow soon after birth were critically important control measures.

Abstract

Paratuberculosis is a chronic bacterial infection of the intestine in cattle caused by Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (Map). To better understand Map transmission in Irish dairy herds, we adapted the French stochastic individual-based epidemiological simulation model to account for seasonal herd demographics. We investigated the probability of Map persistence over time, the within-herd prevalence over time, and the relative importance of transmission pathways, and assessed the relative effectiveness of test-and-cull control strategies.

We investigated the impact on model outputs of calf separation from cows (calves grazed on pasture adjacent to cows vs. were completely separated from cows) and test-and-cull. Test-and-cull scenarios consisted of highly test-positive cows culled within 13 or 4 weeks after detection, and calf born to highly test-positive cows kept vs removed. We simulated a typical Irish dairy herd with on average 82 lactating cows, 112 animals in total. Each scenario was iterated 1000 times to adjust variation caused by stochasticity. Map was introduced in the fully naive herd through the purchase of a moderately infectious primiparous cow. Infection was considered to persist when at least one infected animal remained in the herd or when Map was present in the environment.

The probability of Map persistence 15 years after introduction ranged between 32.2–42.7% when calves and cows had contact on pasture, and between 18.9–29.4% when calves and cows were separated on pasture. The most effective control strategy was to cull highly test-positive cows within four weeks of detection (absolute 10% lower persistence compared to scenarios without control). Removing the offspring of highly test-positive dams did not affect either Map persistence or within-herd prevalence of Map.

Mean prevalence 15 years after Map introduction was highest (63.5 %) when calves and cows had contact on pasture. Mean prevalence was 15 % lower (absolute decrease) when cows were culled within 13 weeks of a high test-positive result, and 28 % lower when culled within 4 weeks. Around calving, the infection rate was high, with calves being infected in utero or via the general indoor environment (most important transmission routes). For the remainder of the year, the incidence rate was relatively low with most calves being infected on pasture when in contact with cows. Testing and culling was an effective control strategy when it was used prior to the calving period to minimize the number of highly infectious cows present when calves were born.

Comments

Animal husbandry systems heavily influence the options for Johne’s disease control measures. This excellent publication is focus on the type of pastoral or gazing type of dairy herd management prevalent in Ireland. It reinforces the importance of culling the cows with high-positive serum ELISA results and prompt separation of calves from cows after birth. Very interested readers should read the section on model assumptions (section 3.7 on page 8) to judge whether they model fits dairy herd management systems in other their country. In the book Empirical Model-Building and Response Surfaces by Box and Draper (1987) they state: “Essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful.” I would rank this model as very useful.

Footnote

ELISAs measure the quantity of antibody in the clinical sample which can be either serum (from blood) or milk (for dairy cows). The ELISA reports numerical results called S/P or S/P% values and values above a certain cut-off are classified as positive. However, much more useful information, beyond positive or negative interpretations, can be had when you examine the magnitude of the ELISA result. Animals in the high range, typically with S/P values over 1.0 or S/P% values over 100 are consider “high-positive”, also called “strong-positive”. Multiple studies have shown that this is important information as cows with high-positive ELISA results are the ones most likely to be shedding the most MAP in their feces and milk and most likely to have infected their unborn fetus. Thus, these are the first cows among all of the ELISA-positive animals that should be culled.

JD CONTROL INCREASES DAIRY PROFIT

2021-01-13 01:00:30 Paul Burden and David Hall from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Calgary, Canada reported on the variations in the profitability of dairy farms in Victoria, Australia by different levels of engagement in bovine Johne’s disease control. Their publication appears in the January 2021 issue of Preventive Veterinary Medicine. Unfortunately, the article is not open access.

Paul Burden and David Hall from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Calgary, Canada reported on the variations in the profitability of dairy farms in Victoria, Australia by different levels of engagement in bovine Johne’s disease control. Their publication appears in the January 2021 issue of Preventive Veterinary Medicine. Unfortunately, the article is not open access.

Abstract

Paratuberculosis or Johne’s disease (JD) prevalence in Australia is low at the cow-level with varying herd-level prevalence. Control strategies incorporating vaccination are limited, suggesting opportunities for changes in regulatory oversight. In order to study this further, we examined the economic benefits of participation in JD control programmes in Australia with and without vaccination as well as knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) relating to JD.

We used an online questionnaire to gather information describing demographics and KAP from 71 Australian dairy farms. Data from fully completed questionnaires from 32 farms in Victoria, Australia combined with cost and revenue data averaged from several years of the Dairy Farm Monitor Project were used to then simulate a larger robust dataset. These production data informed the simulation model to establish farm profitability. A partial farm budget was then developed to estimate the benefits of engaging in JD control activities. Respondents who stated they participated in JD control programmes gained an additional $43.80/cow/year net income (profit) compared to non-participants. Respondents also using a JD vaccine gained an additional $35.84/cow/year over non-users; this represents $10.56/cow/year over and above the average producer in the industry. However, we also noted that there clearly exists a barrier between farmers stated intentions to participate and actual participation in JD control activities.

These significant differences in net income realized by farms using different approaches to JD control (in this case, adoption of vaccination) offer a starting point from which to explore questions of how much farmers would be willing to pay for control activities, why they are willing to pay, and the likelihood of participating. Communication of the benefits of participation needs to improve to bridge this gap between farmers stated intentions and their actions.

Simulation modelling suggests increased profitability from participation in JD control programs and vaccination in Australia. The JD regulatory policies of other countries may benefit from the Australian experience with JD control.

Comments

Vaccination for JD is not an option in many countries of the world, but other Johne’s disease control measures can be done everywhere. Other studies have also shown that JD control improves dairy farm profitability (Roche, Journal of Dairy Science, 2020).

These are the simple steps proven to achieve JD control (see Collins et al. Successful control of Johne’s disease in nine dairy herds: Results of a six-year field trial. J. Dairy Sci, 2010):

- Step #1: have your herd veterinarian do a herd risk assessment to determine which management practices to change in order to limit MAP transmission on the farm.

- Step #2: Implement the necessary management changes with written protocols.

- Step #3: Develop a testing plan with your herd veterinarian coupled to a written “action plan” outlining what will be done with cows based on their JD test results.

JD control is not hard, it simply requires a well-developed plan that is consistently followed for at least 5 years. As the publication by Burden and Hall shows, these actions will significantly improve farm profitability. So, why not do it?

MAP IN PASTEURIZED MILK - IRAN

2021-01-06 01:00:51 Nasim Sadeghi from the Department of Food Hygiene, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, I.R. Iran and 2 colleagues have reported on the detection of MAP in pasteurized milk in northeastern Iran. Their research article appears in most recent issue of the Iranian Journal of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering.

Nasim Sadeghi from the Department of Food Hygiene, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, I.R. Iran and 2 colleagues have reported on the detection of MAP in pasteurized milk in northeastern Iran. Their research article appears in most recent issue of the Iranian Journal of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering.

Abstract

Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis (MAP) is a gram-positive, small, acid-fast bacillus with high environmental resistance. In animals, especially ruminants, it leads to Paratuberculosis (PTB) or Johne's disease, which is chronic granulomatous enteritis. This bacterium as the main causative agent of Crohn's disease can be a serious threat to human health. This study aimed to detect MAP in pasteurized milk samples produced in Khorasan Razavi province, Iran, using Direct Nested PCR, PCR, and culture methods. In this study, 544 milk samples from Pasteurized Milk Production Companies were selected randomly during the 3-month period. DNA was extracted from milk fat after centrifugation. In order to identify the bacteria, Direct Nested PCR and PCR tests were applied using IS900 and f57, respectively. Furthermore, to detect viable MAP, positive samples resulted from Direct Nested PCR assays were cultured on Herrold's egg medium. For identification of mycobacterial isolates, all colonies were processed by PCR based on f57. A total of 544 pasteurized milk samples were assayed, and Mycobacterium paratuberculosis was detected in 39% of them by IS900 Nested PCR, and only 4.9% of samples were positive in the culture method. All the colonies were positive for the f57 using PCR. The results of this study indirectly indicated a high level of contamination of pasteurized milk to Mycobacterium paratuberculosis which is due to the large number of affected animals in livestock farms in Khorasan Razavi province. However, in comparison with the other researches, the low percentage of viable bacteria in pasteurized milk can be due to changes in temperature and time in pasteurizing systems of milk production companies in Khorasan Razavi province, Northeast of Iran.

Comment

When it comes to MAP, pasteurization is not perfect. The body of scientific evidence that viable (living) MAP occur in retail pasteurized dairy products continues to grow making this an important food safety issue. Rates of MAP detection by PCR methods, which do not distinguish living from dead MAP, are much higher than when using culture-based methods that detect only live MAP, as shown in the Iranian study. As new non-culture-based methods for detection of live MAP in dairy products are developed, I anticipate there will be even higher rates of viable MAP detection in dairy products. Also, the expanding paratuberculosis epidemic in animals globally results in steadily rising levels of MAP in all foods of animal-origin.

It is also important to consider that dead MAP in food may act as an allergen for some people potentially triggering inflammatory responses leading to diseases such as Type 1 Diabetes that are presently consider autoimmune disease. The cell walls of mycobacteria harbor some of the most potent immunogens known and have been used in Freund’s complete adjuvant to bolster immune responses to other antigens to produce high levels of antibodies in animals for decades.

Here is a partial list other published studies that have found live MAP in retail pasteurized milk:

- United Kingdom, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, May 2002.

- United States, Journal of Food Protection, May 2005.

- Czech Republic, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, March 2005.

- India, International Journal of Infectious Diseases, February 2010.

- Argentina, Brazilian Journal of Microbiology, July 2012.

- Brazil, Journal of Dairy Science, December 2012.

In closing…..

- Please forward the link to this news item to others you know who might be interested.

- Please subscribe to this website if you want to get regular emails about news items and content additions to the site.

- Please consider donating to help sustain this website.

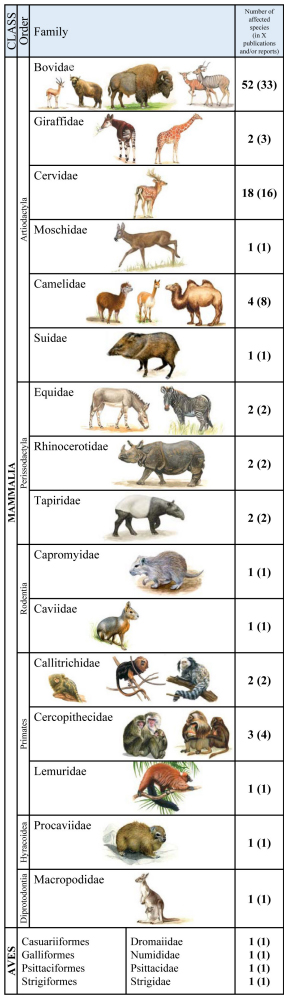

MAP IN ZOO ANIMALS – REVIEW

2020-12-30 01:01:25Marco Roller and six colleagues in Germany and Brazil have published an excellent review article on MAP infections in zoo animals. This Open Access article appears in Frontiers in Veterinary Science (19 pages; 171 references).

ABSTRACT

Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) is the causative agent of paratuberculosis (ParaTB or Johne’s disease), a contagious, chronic and typically fatal enteric disease of domestic and non-domestic ruminants. Clinically affected animals present wasting and emaciation. However, MAP can also infect non-ruminant animal species with less specific signs. Zoological gardens harbor various populations of diverse animal species, which are managed on limited space at higher than natural densities. Hence, they are predisposed to endemic trans-species pathogen distribution. Information about the incidence and prevalence of MAP infections in zoological gardens and the resulting potential threat to exotic and endangered species are rare. Due to unclear pathogenesis, chronicity of disease as well as the unknown cross-species accuracy of diagnostic tests, diagnosis and surveillance of MAP and ParaTB is challenging. Differentiation between uninfected shedders of ingested bacteria; subclinically infected individuals; and preclinically diseased animals, which may subsequently develop clinical signs after long incubation periods, is crucial for the interpretation of positive test results in animals and the resulting consequences in their management. This review summarizes published data from the current literature on occurrence of MAP infection and disease in susceptible and affected zoo animal species as well as the applied diagnostic methods and measures. Clinical signs indicative for ParaTB, pathological findings and reports on detection, transmission and epidemiology in zoo animals are included. Furthermore, case reports were re-evaluated for incorporation into accepted consistent terminologies and case definitions.

Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) is the causative agent of paratuberculosis (ParaTB or Johne’s disease), a contagious, chronic and typically fatal enteric disease of domestic and non-domestic ruminants. Clinically affected animals present wasting and emaciation. However, MAP can also infect non-ruminant animal species with less specific signs. Zoological gardens harbor various populations of diverse animal species, which are managed on limited space at higher than natural densities. Hence, they are predisposed to endemic trans-species pathogen distribution. Information about the incidence and prevalence of MAP infections in zoological gardens and the resulting potential threat to exotic and endangered species are rare. Due to unclear pathogenesis, chronicity of disease as well as the unknown cross-species accuracy of diagnostic tests, diagnosis and surveillance of MAP and ParaTB is challenging. Differentiation between uninfected shedders of ingested bacteria; subclinically infected individuals; and preclinically diseased animals, which may subsequently develop clinical signs after long incubation periods, is crucial for the interpretation of positive test results in animals and the resulting consequences in their management. This review summarizes published data from the current literature on occurrence of MAP infection and disease in susceptible and affected zoo animal species as well as the applied diagnostic methods and measures. Clinical signs indicative for ParaTB, pathological findings and reports on detection, transmission and epidemiology in zoo animals are included. Furthermore, case reports were re-evaluated for incorporation into accepted consistent terminologies and case definitions.

COMMENT

At least half of zoos in North America have had animals diagnosed with Johne’s disease. The infection spreads among institutions by the trade of animals; a practice that is essential for captive breeding programs. This led to a meeting of major zoo veterinarians and other zoo staff at the White Oak Conservation Center in Yulee, Florida in 1998. The 17-page proceedings of that meeting laid the groundwork for the control and prevention of Johne’s disease in zoological institutions. The White Oak proceedings are frequently cited in this publication by Rollo et al. Because these proceedings are hard to access, I have made it available here and on the website page about MAP infections of zoo ruminants.

MAP IN MANY HUMANS

2020-12-23 16:50:58Dr. J. Todd Kuenstner, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, and colleagues from seven other institutions have reported on the detection of MAP in the blood of people with and without Crohn’s Disease by multiple laboratory assays. Their article appears in the most recent issue of Microorganisms [Open Access, 14 pages with 51 references].

Abstract

Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) has long been suspected to be involved in the etiology of Crohn’s disease (CD). An obligate intracellular pathogen, MAP persists and influences host macrophages. The primary goals of this study were to test new rapid culture methods for MAP in human subjects and to assess the degree of viable culturable MAP bacteremia in CD patients compared to controls. A secondary goal was to compare the efficacy of three culture methods plus a phage assay and four antibody assays performed in separate laboratories, to detect MAP from the parallel samples. Culture and serological MAP testing was performed blind on whole blood samples obtained from 201 subjects including 61 CD patients (two of the patients with CD had concurrent ulcerative colitis (UC)) and 140 non-CD controls (14 patients in this group had UC only).

Viable MAP bacteremia was detected in a significant number of study subjects across all groups. This included Pozzato culture (124/201 or 62% of all subjects, 35/61 or 57% of CD patients), Phage assay (113/201 or 56% of all subjects, 28/61 or 46% of CD patients), TiKa culture (64/201 or 32% of all subjects, 22/61 or 36% of CD patients) and MGIT culture (36/201 or 18% of all subjects, 15/61 or 25% of CD patients). A link between MAP detection and CD was observed with MGIT culture and one of the antibody methods (Hsp65) confirming previous studies. Other detection methods showed

no association between any of the groups tested. Nine subjects with a positive Phage assay (4/9) or MAP culture (5/9) were again positive with the Phage assay one year later. This study highlights viable MAP bacteremia is widespread in the study population including CD patients, those with other autoimmune conditions and asymptomatic healthy subjects.

Comment

While the high rate of MAP detection in human blood samples is shocking, it is not surprising. MAP has been proven capable of infecting a wide array of animal species, including nonhuman primates. The majority of MAP-infected animals, e.g., cattle, goats and sheep, are used for food. Since food safety regulatory agencies have not declared MAP to be a zoonotic pathogen, those MAP-infected animals, and their products such as milk, legally enter the food supply daily. Multiple studies have detected live MAP in retail pasteurized milk, cheese, and meat. Thus, humans are being exposed every day.

As the concluding sentence of this Dr. Kuenstner’s publication states: “as a minimum measure of best practice, the possibility that MAP is a zoonotic pathogen should prompt public health measures to better control JD and MAP spread into food and the environment by governments worldwide."

For more on MAP as a human pathogen visit the website of the Human Para Foundation, the organization who funded this study.

Read this for more evidence that MAP is a zoonotic pathogen.

Read this for more on MAP in food and water.

WHY I DO THIS

2020-12-18 01:06:40Once upon a time, about 17 years ago, there was a young Wisconsin girl named Lizi who was in 4H, a U.S. organization that provides experiences where young people learn by doing. Lizi decided to do a project to learn more about Johne's disease, something she had seen on her family's farm. She searched the web and found Johnes.org. Lizi used the information and images she found there to create a poster which she exhibited at the Lodi Agricultural Fair and Dane County Fair in Wisconsin, winning a blue ribbon for her efforts. Here is a picture of Lizi's poster.

This story came to light when Lizi was in my Veterinary Bacteriology & Mycology class, Fall semester in 2017, learning (again) about Johne's disease. Lizi shared this picture of her poster and granted me permission to tell her story.

The adjacent photo shows Lizi with a newborn calf on her family's farm. She graduated with her DVM degree from the University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine, May, 2020. She is pursuing a career in food animal medicine.

You never know what kind of impact knowledge sharing will have.

That is why I do this.

Michael T. Collins, DVM, PhD, DACVM

Comment: 4‑H is delivered by Cooperative Extension—a community of more than 100 public universities across the nation that provides experiences where young people learn by doing. For more than 100 years, 4‑H has welcomed young people of all beliefs and backgrounds, giving kids a voice to express who they are and how they make their lives and communities better.

If you feel you have seen this news posting before, you are not losing your mind. I originally posted this after Lizi was in my class and made me aware of our connection. In these tough times I feel that some heart-warming news like this is worth re-posting.

« Previous 1 … 4 5 6 7 8 … 18 Next »